Amedeo Modigliani Timeline (1906-1920)

This detailed timeline traces the artistic life of Amedeo Modigliani from his arrival in Paris in 1906 until his death in 1920. Unlike a conventional biography, this chronology focuses on what Modigliani was making, who he was painting, and how his style evolved year by year.

It places his most famous works — including the celebrated nude series, elongated portraits, and sculptural experiments — into clear historical context, linking each period to specific paintings, sitters, dealers, and personal events.

By following Modigliani's career chronologically, patterns emerge: the shift from sculpture to painting, the sudden explosion of nudes in 1917, and the central role played by Jeanne Hébuterne during his final years. This timeline also serves as a navigational hub, connecting Modigliani's key works, relationships, and artistic phases.

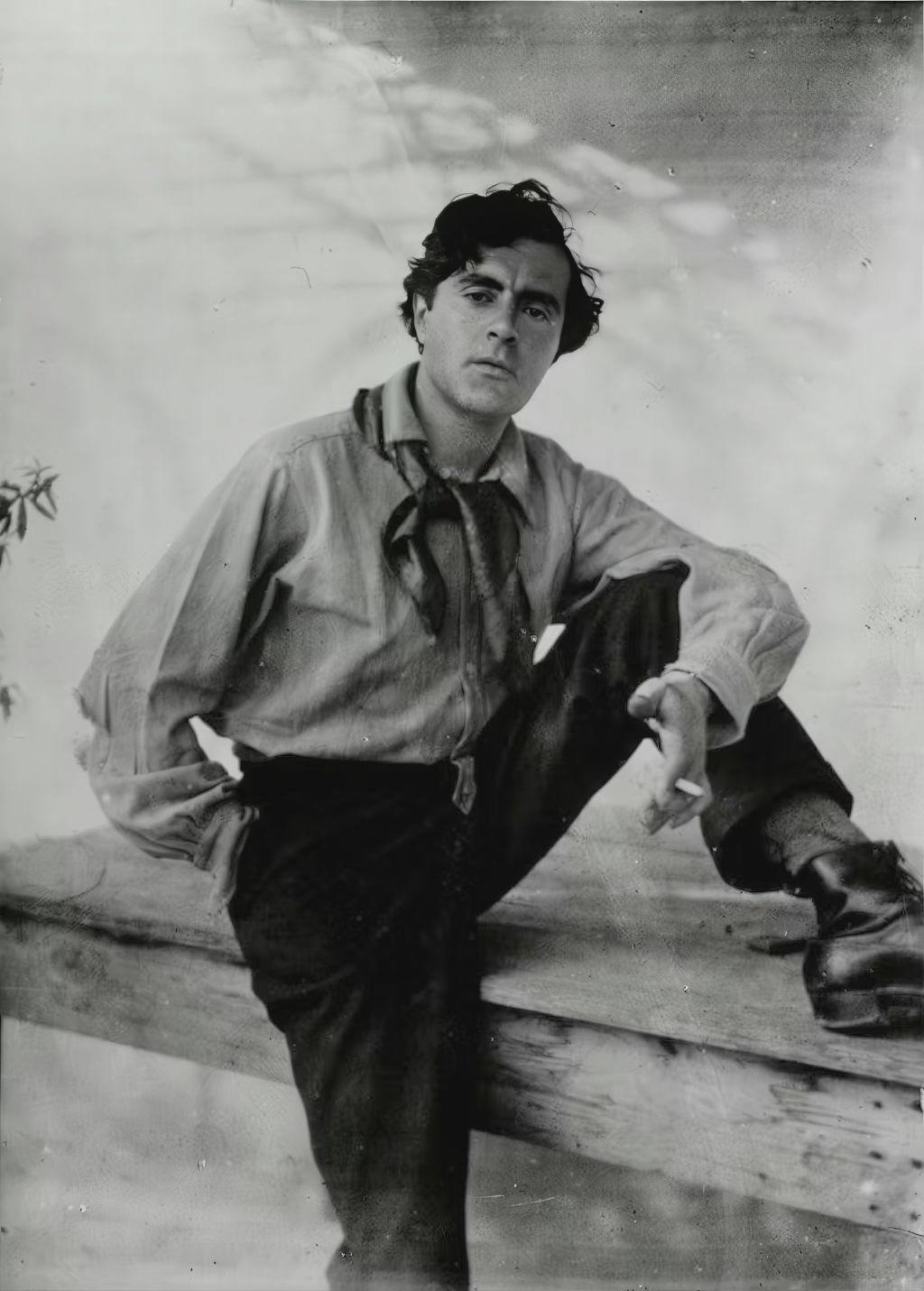

1906 — Arrival in Paris and First Encounters

In January 1906, Amedeo Modigliani arrives in Paris, settling initially in Montmartre, then the epicentre of the European avant-garde. Paris exposes him to a density of artistic innovation unavailable in Italy: Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Symbolism, and the earliest stages of Cubism coexist within a few streets.

Modigliani briefly enrolls at the Académie Colarossi and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. However, his temperament and fragile health make sustained academic training impossible. Instead, he studies independently in museums, cafés, and studios, absorbing influences from Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec, and archaic sculpture.

This year establishes a lifelong pattern: Modigliani remains socially immersed in the avant-garde while stylistically isolated, pursuing a personal vision rather than aligning with any movement.

1907 — Search for Identity and Form

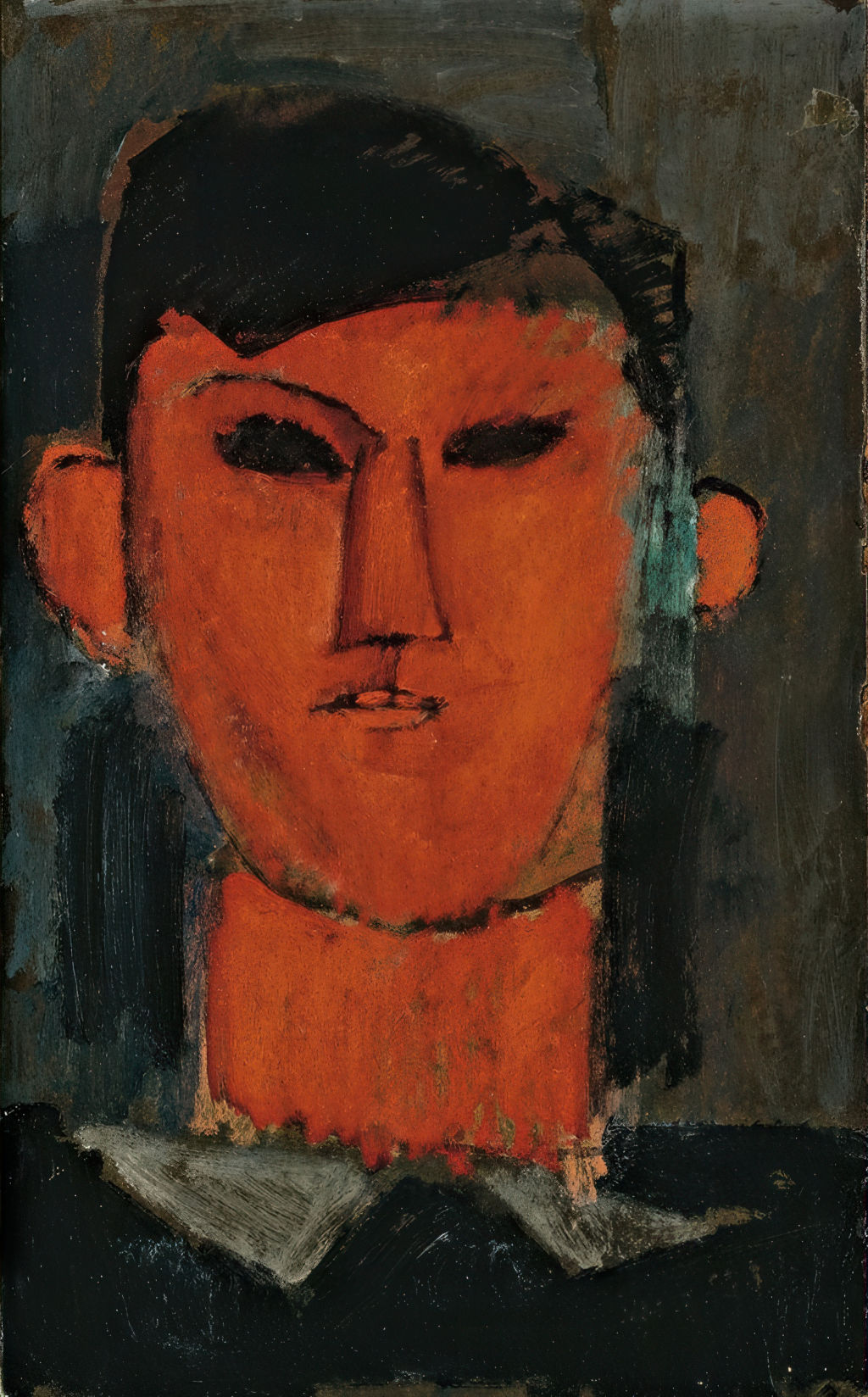

By 1907, Modigliani is producing portraits and figure studies marked by dark tonalities and expressive brushwork. These early works often feel introspective, reflecting his own precarious position as an immigrant artist in Paris.

His encounters with African masks and non-Western art at the Trocadéro ethnographic museum prove decisive. The abstraction of facial features, emphasis on contour, and symbolic distortion of anatomy begin to replace naturalistic modelling.

Though few works from this year are firmly dated, they reveal a growing concern with the psychological presence of the sitter rather than likeness alone.

1908 — Early Portraits and Cultural Identity

In 1908, Modigliani paints several works that address identity and marginalisation. Paintings such as Jewish Woman belong to this moment, combining sombre colour with a direct, frontal presentation of the sitter.

These works engage indirectly with Modigliani's own Jewish heritage and outsider status in Paris. Rather than caricature or sentimentality, the figures are dignified, restrained, and psychologically complex.

Stylistically, line begins to dominate over colour. Facial features elongate, backgrounds flatten, and the figure is increasingly isolated from narrative context.

1909 — Turn Toward Sculpture

Around 1909, Modigliani undergoes a radical shift, turning away from painting to concentrate almost exclusively on sculpture. His close friendship with Constantin Brancusi plays a central role in this transition.

Working primarily in stone, Modigliani carves elongated heads characterised by simplified planes, almond-shaped eyes, and columnar necks. These heads draw equally from African masks, Cycladic idols, and archaic Greek sculpture.

Sculpture offers Modigliani what painting had not yet provided: a sense of permanence, structure, and monumentality.

1910 — Sculptural Immersion

Throughout 1910, Modigliani deepens his commitment to sculpture, often working outdoors due to dust and noise. Friends later recall him scavenging stone blocks from construction sites, carving obsessively despite his failing health.

The act of carving becomes central to his artistic philosophy. Modigliani begins to conceive of form as something revealed rather than constructed — a concept that later informs his painted portraits.

Although few sculptures survive, this year establishes the vocabulary that defines his mature style.

1911 — Caryatids and Architectural Ambition

By 1911, Modigliani is fully engaged with the idea of caryatids — stylised female figures intended as architectural supports.

He produces dozens of drawings exploring kneeling, standing, and squatting female forms, often repeating the same pose with subtle variations. These drawings show a rhythmic, almost musical repetition of line.

The caryatids reflect Modigliani's ambition to transcend easel painting and create a unified sculptural environment, though the project remains unrealised.

1912 — Peak of the Sculptural Vision

1912 marks the height of Modigliani's sculptural period. He exhibits several stone heads at the Salon d'Automne, receiving limited attention but confirming his seriousness as a sculptor.

At the same time, his health deteriorates significantly. Tuberculosis, aggravated by physical labour, increasingly limits his capacity to carve.

Despite this, the sculptural ideals developed during this period permanently shape his approach to painting.

1913 — Decline of Sculpture, Persistence of Drawing

By 1913, Modigliani produces fewer sculptures but continues to draw caryatids obsessively.

These drawings serve as a bridge between sculpture and painting, translating carved volume into linear rhythm.

Financial hardship intensifies, and Modigliani becomes increasingly dependent on patrons and friends.

1914 — Return to Painting Amid War

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 coincides with Modigliani's reluctant abandonment of sculpture.

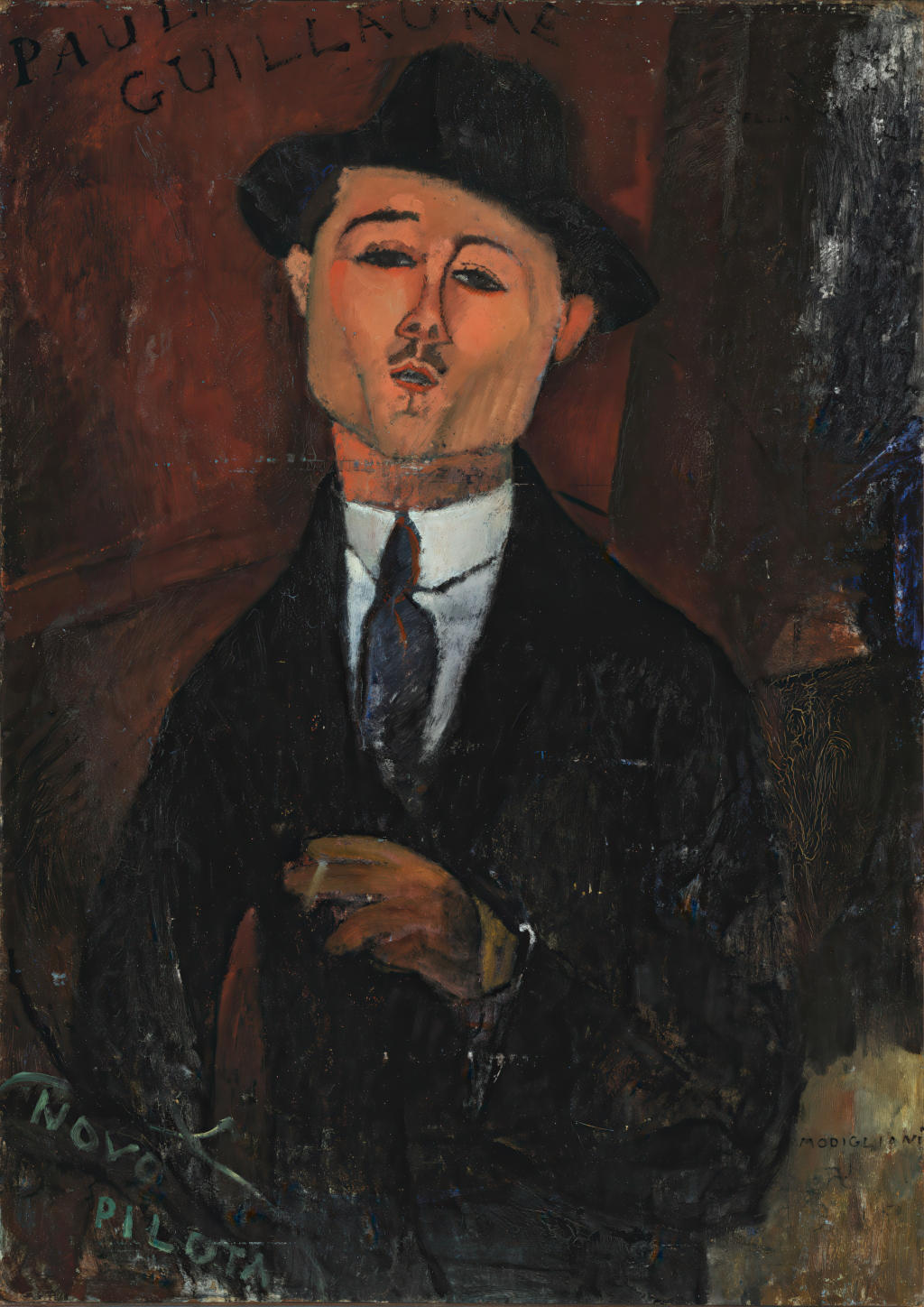

He returns decisively to painting, now equipped with a sculptor's understanding of structure. Portraits from this year show greater clarity of outline, reduced modelling, and flattened backgrounds.

The war disrupts artistic networks, but Modigliani remains in Paris, painting steadily.

1915 — Emergence of the Mature Portrait Style

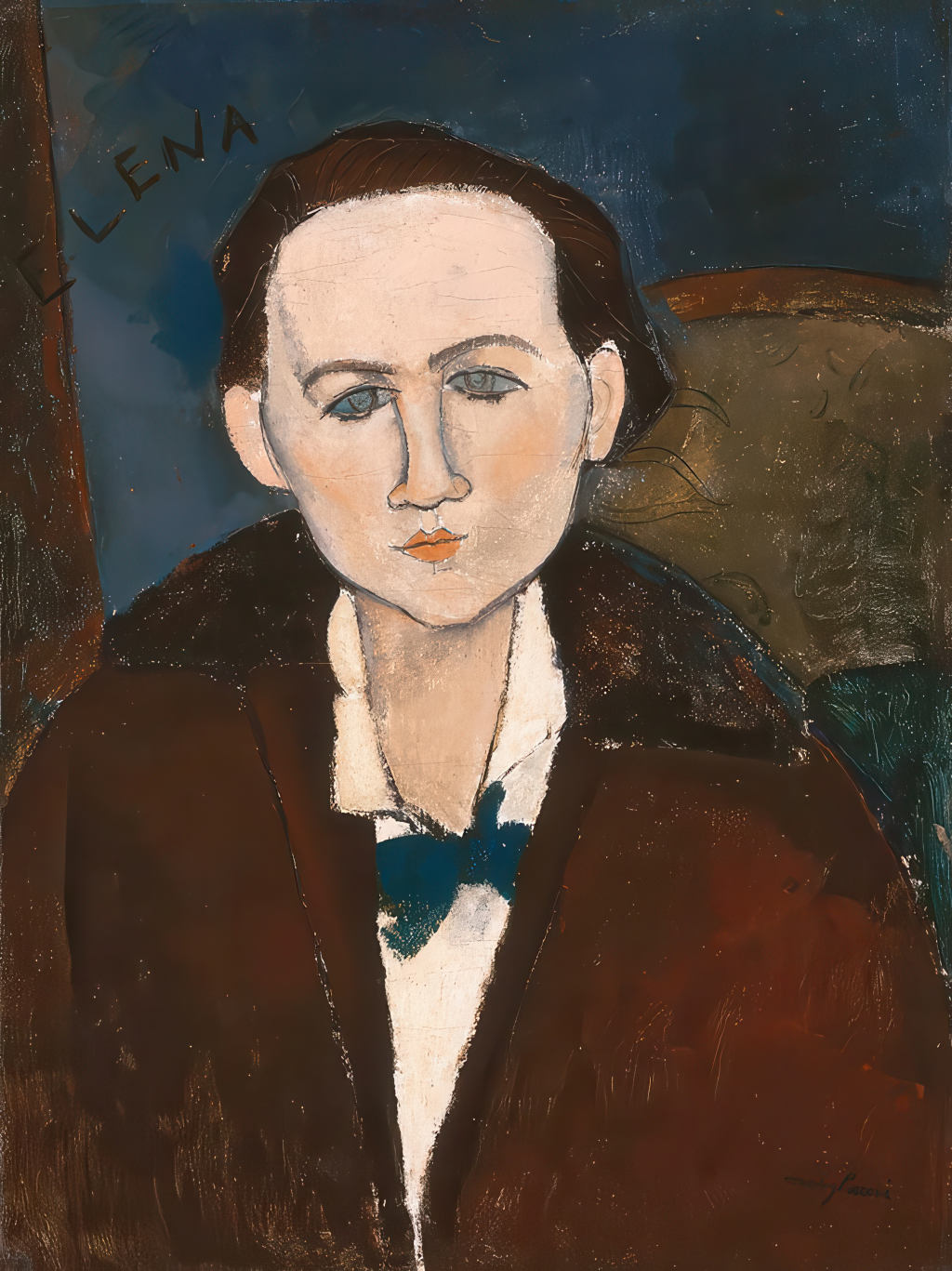

In 1915, Modigliani's signature portrait style becomes fully recognisable.

Faces elongate dramatically, noses form continuous vertical lines, and eyes become stylised ovals — sometimes blank, sometimes asymmetrical.

Portraits from this year prioritise emotional distance and timelessness over anecdotal detail.

1916 — Jeanne Hébuterne Enters His Life

Modigliani meets Jeanne Hébuterne in 1916. Their relationship profoundly affects both his personal life and artistic output.

Jeanne appears repeatedly in his paintings, her long neck and oval face aligning perfectly with his idealised proportions.

This year also marks increased support from dealer Léopold Zborowski, stabilising Modigliani's production.

1917 — The Nude Series and Public Scandal

1917 represents the most intense and concentrated period of Modigliani's career.

Encouraged by Zborowski, he produces a series of reclining and seated nudes that redefine the modern nude.

Unlike classical precedents, these nudes confront the viewer directly, their sexuality neither mythologised nor concealed.

The police closure of his exhibition at Galerie Berthe Weill cements his reputation as a controversial modern artist.

1918 — Exile in the South of France

In 1918, Modigliani and Jeanne Hébuterne relocate to Nice.

The Mediterranean light softens his palette, though his compositional structure remains consistent.

Jeanne gives birth to their daughter, providing brief emotional stability.

1919 — Final Paris Works

Returning to Paris in 1919, Modigliani is visibly ill but continues working with urgency.

Portraits from this year are often quieter, more restrained, and psychologically distant.

Jeanne Hébuterne, pregnant again, dominates his final body of work.

1920 — Death and Legacy

Modigliani dies on 24 January 1920 from tubercular meningitis.

Jeanne Hébuterne's suicide two days later becomes inseparable from his legacy.

Posthumously, Modigliani's reputation rises rapidly, his nudes and portraits becoming icons of modern art.